When my biological mother was carrying me, she was struggling with three children and an alcoholic spouse. In her eighth month of pregnancy, she was starting to get really burdened. Her uncle and his wife couldn’t have children of their own, so they came up with a deal. My mother said, “I’ll give up this child to you, but you have to teach him to carve.”

After both of my mothers passed away, I was put in foster care at the age of four. When my grandfather got wind of it he walked 16 kilometers from Sunnyside Cannery into Prince Rupert and demanded me back.

I discovered I had carvers on both sides of my family tree, both maternal and paternal. My father, Patterson McKay, started sending me books of totem poles and First Nations Indigenous design—formline we call it today. My grandmother got me to draw every picture in those books.

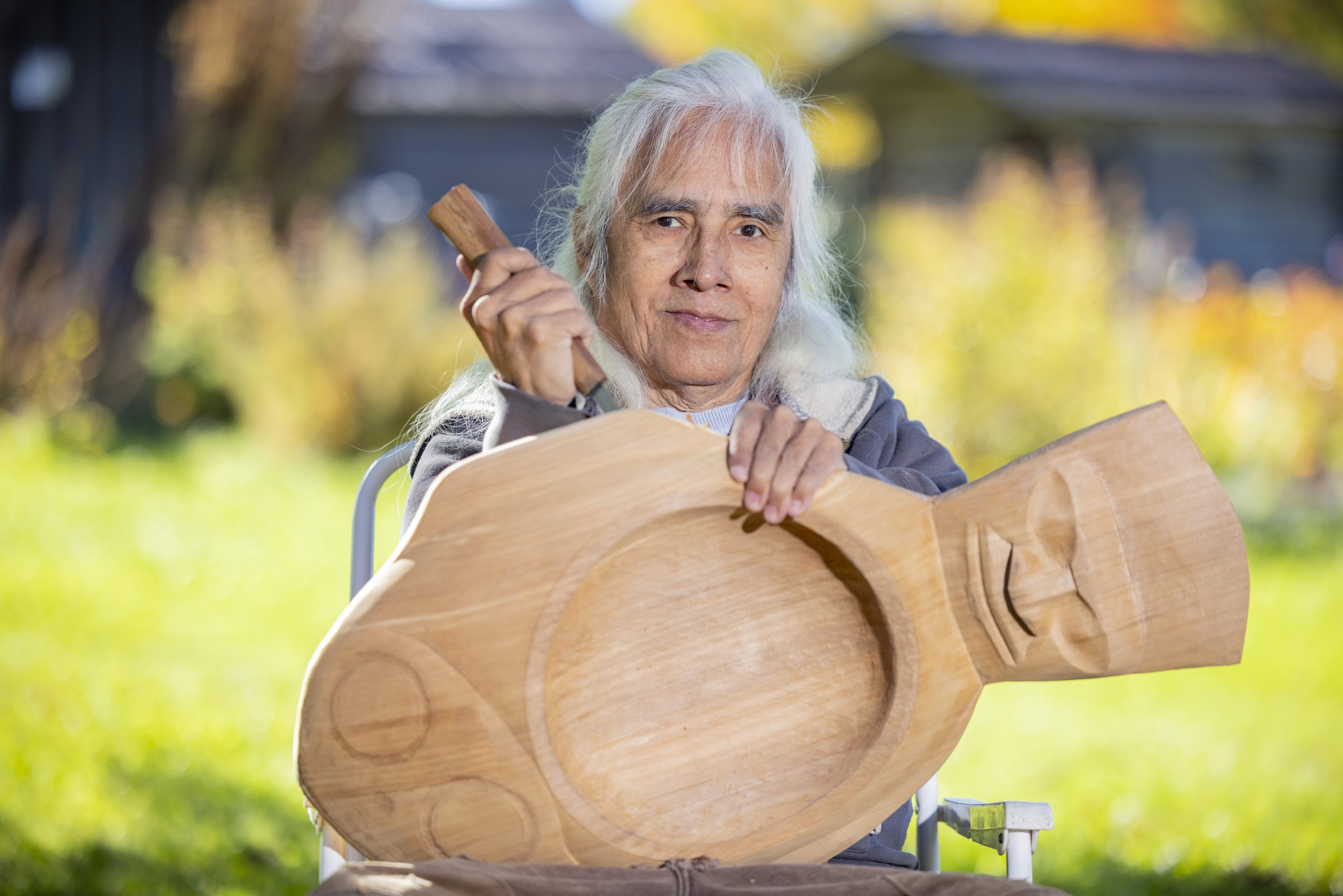

In the summertime, I would go back to Prince Rupert and live with my dad. I found myself in a house full of carvers. There were carvers from Haida Gwaii, the Skeena River, and the Nass River all carving in that little two bedroom house. So that’s where my initial training began. I started sanding for the carvers. I was getting the feel of the wood, the contours, the curvature.

When I was 12 years old, I was carving down on the boardwalk at the old ferry terminal in Prince Rupert. A couple traveling on the ferry to Alaska came down and bought everything I had—nine plaques. Almost 25 years later, I walked into a gallery in Juneau, Alaska and they recognized my signature. The guy’s eyes lit up and he said, “We want you to come to our house for dinner.”

I remember that Christmas I discovered my father was going blind. I watched him cut his fingers as he was trying to carve. I said, “Dad, let me try.” And he looked at me and said, “I was waiting to hear those words.” That’s when I took his spot. I keep that in my mind. I keep it in my heart that I was born for this job.

The biggest pole I ever carved was 40 feet and it stands in the Village of Lax̱g̱alts’ap. It’s called the Unity Pole. My late uncle and I carved it the same year my father passed away.

If you want to be a carver, follow the bloodline. Study your culture, your heritage, your artistic style. It’s called identity. Knowing who you are and where you come from. That’s what I teach today.